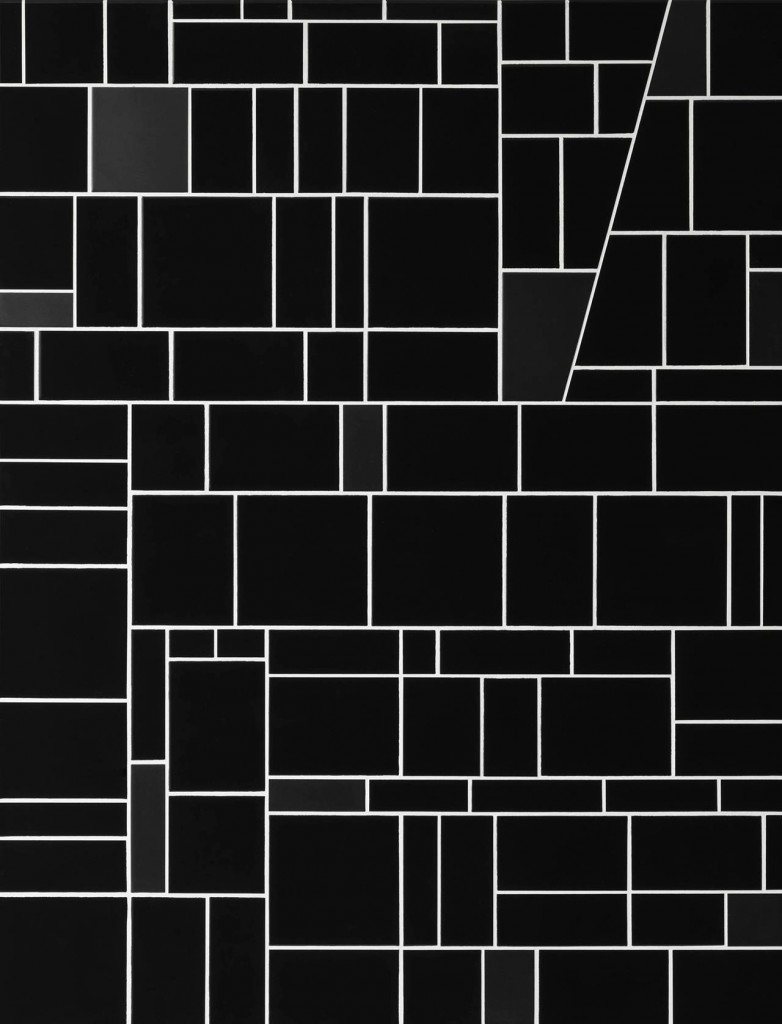

Lars Dittrich and André Schlechtriem are pleased to present DIE FUGE, by Simon Mullan. For his first solo-exhibition with the gallery in Berlin, Mullan has prepared an ambitious intervention spanning all 4 rooms of the gallery space. Continuing his signature aesthetic of segmented and coded utilitarian materials, the artist has completely reconstructed the front walls of the gallery space using ceramic white tiles with an Anthracite grey grout. This seemingly indiscriminate middle-grey then replaces the standard white walls of the remaining gallery space, repurposed as the backdrop to 4 new contrasting black tiled wall-objets from his series Popularis and 2 pendulous soft sculptures of altered Alpha Industries bomber jackets.

“Simon Mullan’s spaces investigate the grids of a perspective on art history, its intersections and -faces with the continuum. They flow because they are conscientiously paved. Mullan’s spaces are absolute spaces, tiled, gridded, topologically reversibly unequivocal, suitable for Euclidean operation, geometrically rectilinear, rinse-off, clinical, glossy and matte, gray.“

With the Popularis series, Mullan works “with the fugacious joints, the synaptic clefts in which transmission takes place. The joint joins and separates: it is pure distinction, the scene of the critic’s craft, in the literal sense of the Greek “kritiké tékhne,” of “krínein,” of distinguishing and setting apart. The tile setter orders the cosmos (Greek for “adornment, jewelry”) and lays it out like an oracle: Everything flows. Everything is installation art (…).

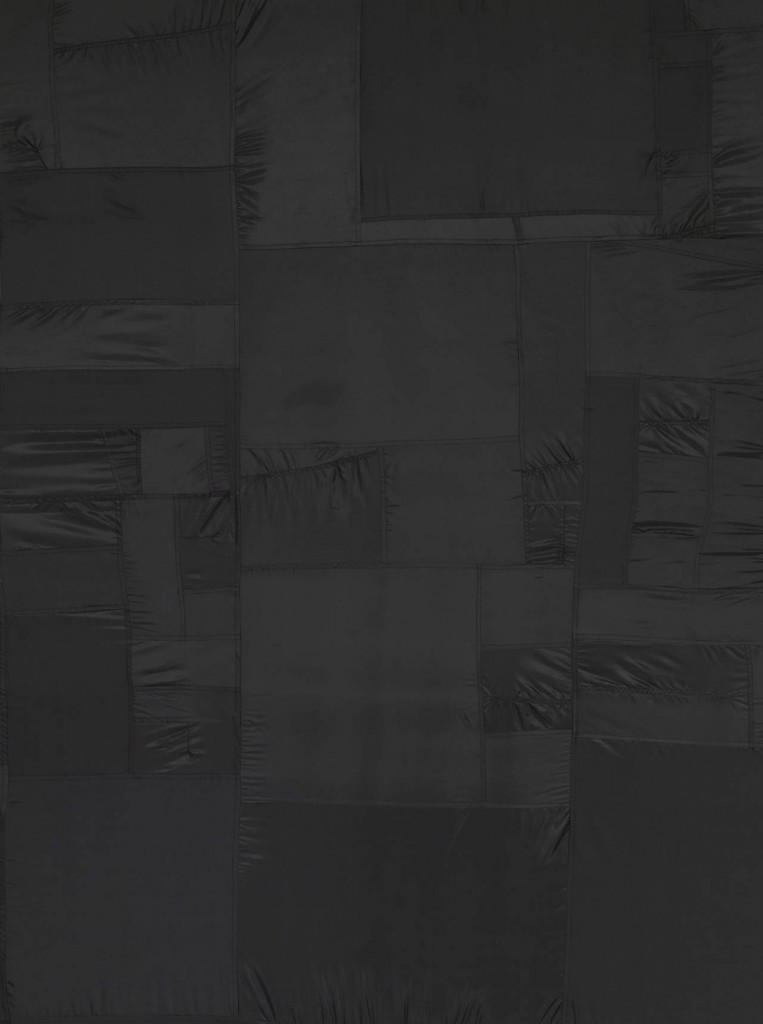

The works in the Alpha series, patchwork constructions out of fabric parts taken from the classic MA-1 flight jacket—the iconic garment better known as the bomber jacket—call several traditions to mind. They share the cartographic quality of the Popularis, though they resemble nothing so much as aerial photographs of endless fields of industrial food production, capturing possible targets of those bombers as well as satellite surveillance scenarios and the hunger for completeness that drives Google Earth and similar ventures. But the same patterns serve as camouflage against those image recognition programs as well.

They are also quilts, social mosaics of different subcultures from the second half of the twentieth century ranging from army and air force uniforms across punks, skinheads, and mods to neo-Nazis and the gay fetish scene, from everyday apparel worn primarily by the working class to the elementary essential high fashion object that the jacket, usually manufactured by Alpha Industries but copied and quoted by both upmarket and downmarket competitors, has become.”

The above excerpts from the essay “Die Fuge“ by Paul Feigelfeld are featured in the full exhibition catalog available through the gallery. The exhibition will also be featured in the forthcoming catalog on the artist produced by the Haubrok Foundation, Berlin. Please contact Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com, for press information and with any further inquiries.

Simon Mullan (b. Kiel, DE / 1981) currently lives and works in London. Mullan studied Transmedial Art at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna and Video Art at The Royal University College of Fine Art Stockholm. His work has been presented internationally with solo exhibitions in London, Stockholm, and Berlin and was recently included in the OFF Biennale / Cairo, Egypt curated by Power Ekroth.

Lars Dittrich und André Schlechtriem freuen sich, Ihnen die Ausstellung DIE FUGE von Simon Mullan zu präsentieren. In seiner ersten Einzelausstellung in den Galerieräumen von DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM hat Mullan ein Präsentationskonzept entwickelt, das sich über die gesamte Ausstellungfläche erstreckt und an seine Auseinandersetzung mit segmentierten und sozial kodierten Materialästhetiken früherer Werke anknüpft. Dazu hat er den vorderen Raum der Galerie komplett in weißen Keramikfliesen gefließt und die Antrazit-Graue Farbe der Fugen als Farbflächen auf die restlichen Galerieräume übertragen. Diese sich wiederholende Farbgebung dient als Hintergrund für die neuen Arbeiten Mullans: Vier schwarz geflieste Wandobjekte aus der Serie “Popularis” und zwei textile Skulpturen umgenähter Alpha Industries Bomberjacken.

“Simon Mullans Räume fahnden nach den Rastern der Perspektive auf eine Kunstgeschichte, ihren Schnitten und Stellen mit dem Kontinuum. Sie fließen, weil sie geflissentlich gefliest sind. Mullans Räume sind absolute Räume, gekachelt, gerastert, topologisch eineindeutig, euklidisch operativ, geometrisch geradlinig, abwaschbar, klinisch, glänzend und matt, grau.“

Mit der „Popularis“ Serie arbeitet Mullan in „den flüchtigen Fugen, den synaptischen Spalten, in denen übertragen wird. Die Fuge hält zusammen und auseinander: Sie ist reine Unterscheidung, sie ist der Ort kritischen Handwerks ganz im Sinne der griechischen „kritiké téchne“, des „krínein“, des Unterscheidens und Trennens. Der Fliesenleger ordnet den Kosmos (griechisch „Schmuck, Geschmeide“) und legt ihn aus wie ein Orakel: Alles fließt. Alles ist Installationskunst. (…)

Die Arbeiten aus der Serie „Alpha“, zusammengenähte Stoffteile der klassischen MA-1 Flieger- oder gemeinhin als Bomberjacke ikonisch gewordenen Jacke, rufen verschiedene Traditionen auf. Sie kartografieren ebenso wie „Popularis“, sind dabei jedoch vielleicht eher Luftbildfotografien endloser Felder industrieller Lebensmittelproduktion – mögliches Ziel ebenjener Bomber, jedoch auch Überwachungsszenarien durch Satelliten oder die Vollständigkeitsbegierden etwa von Google Earth finden sich hier. Die Pattern dienen aber auch als Camouflage gegen eben diese Bilderkennungssoftwares.

Auch sind sie Quilts, soziale Mosaike unterschiedlicher Subkulturen der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, vom Uniformen der Armee und der Luftwaffe über Punks, Skinheads und Mods hin zu Neonazis und der schwulen Fetischszene, vom alltäglichen Kleidungsstück vorwiegend der Arbeiterklasse zum elementar essentiellen High-Fashion-Objekt, das die meist von der Firma Alpha Industries hergestellte, aber vielfach nach unten und oben kopierte und zitierte Jacke heute ist.“

Die Textauszüge stammen aus Paul Feigelfelds Essay „Die Fuge“, der zur Eröffnung im Ausstellungskatalog von DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM publiziert wird. Die Ausstellung wird ebenfalls in einem Katalog zu Simon Mullan von der Haubrok Foundation in Berlin veröffentlicht. Für Presseinformationen und bei weiteren Fragen wenden Sie sich bitte an Owen Clements, owen@dittrich-schlechtriem.com

Simon Mullan (geb. Kiel, DE / 1981) lebt und arbeitet in London. Mullan studierte Transmedial Art an der Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien und Video Art an der Königlichen Hochschule für Künste, Stockholm. Seine Arbeiten wurden in internationalen Einzelausstellungen in London, Stockholm und Berlin ausgestellt und kürzlich auf der von Power Ekroth kuratierten OFF Biennale / Kairo, Ägypten gezeigt.