Like his contemporary and (now much more famous) rival Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke (1635–1702) was a seventeenth- century polymath. After his father killed himself, Hooke was destined to become a painter, but he could not stand the smell of oil paint. He chose to become a scientist instead and as such took an interest in virtually everything: he built a diving bell, microscopes, and telescopes, experimented with blood transfusions, recognized the compound nature of insects’ eyes, coined the term “cell”—and laid the foundations of modern meteorology. His paper “A Method for Making a History of the Weather” (1663) contained the first rigorous and detailed instructions on meteorological observation. Half a year later, he presented it to the Royal Society, a learned society of which he was a member, and was tasked with observing the weather and perhaps devise ways to predict it. To this end, he developed a series of meteorological instruments. In 1679, he constructed a complete weather station. Hooke’s weather clock recorded wind velocity, precipitation, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure on a paper strip—automatically. The idea of mechanizing meteorological observation and thus eliminating the need for a human agent and his subjective notation was three hundred years ahead of its time.2 Hooke also realized the need to observe the weather with a network of such stations that should ideally be installed all over the world.

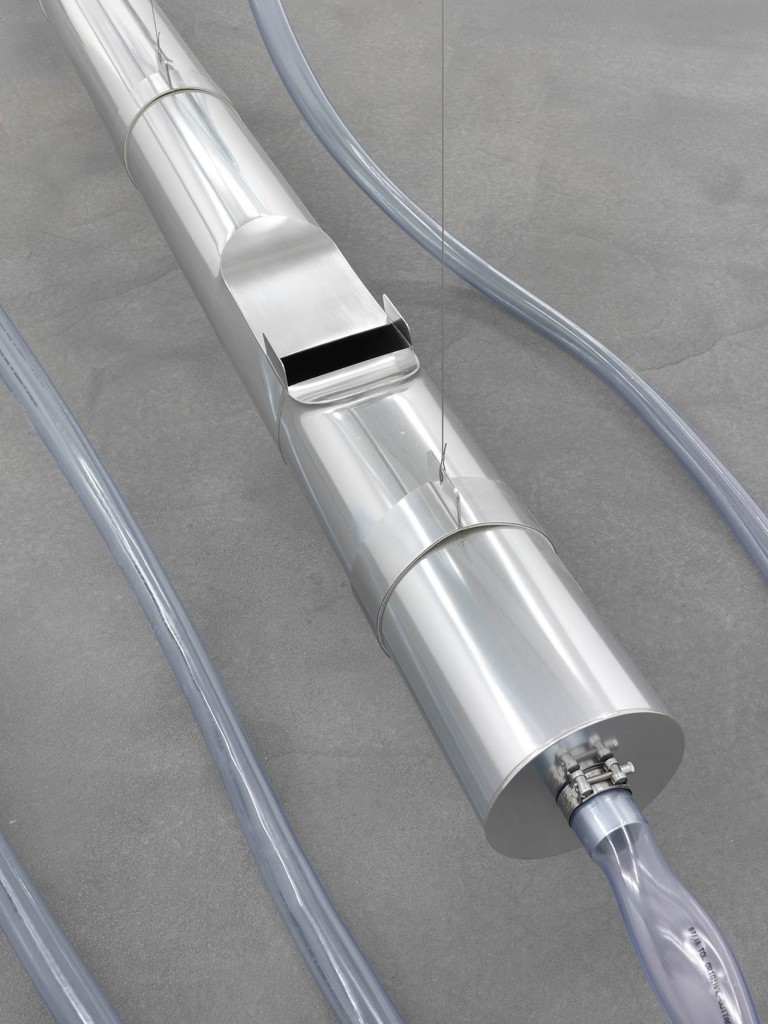

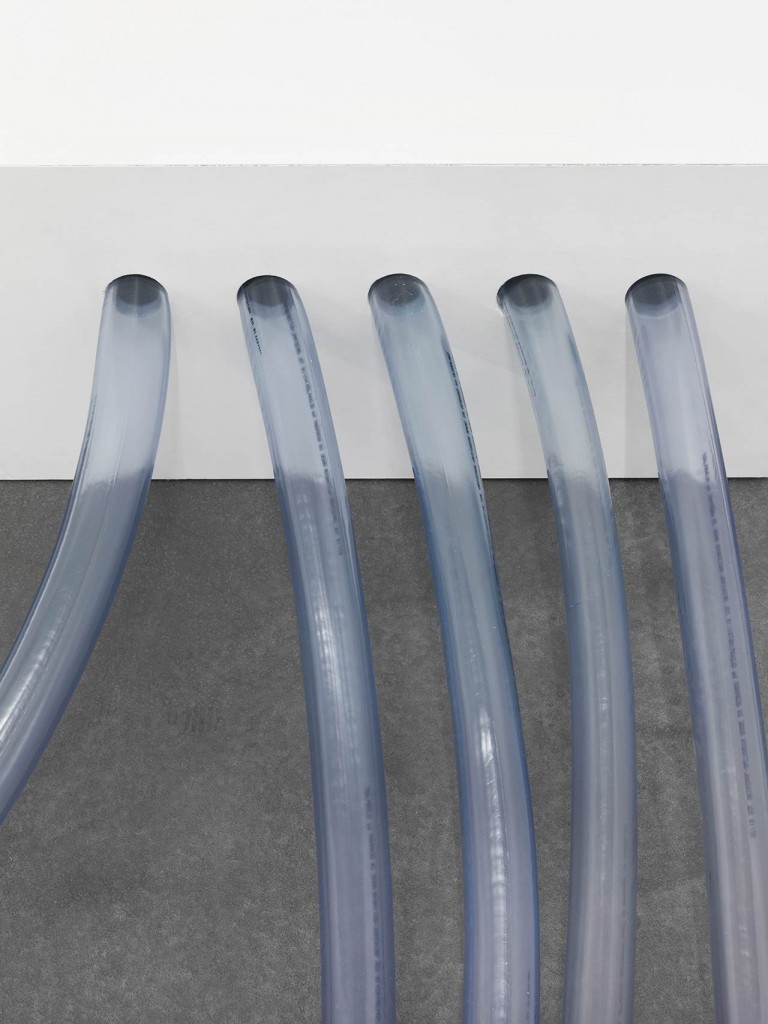

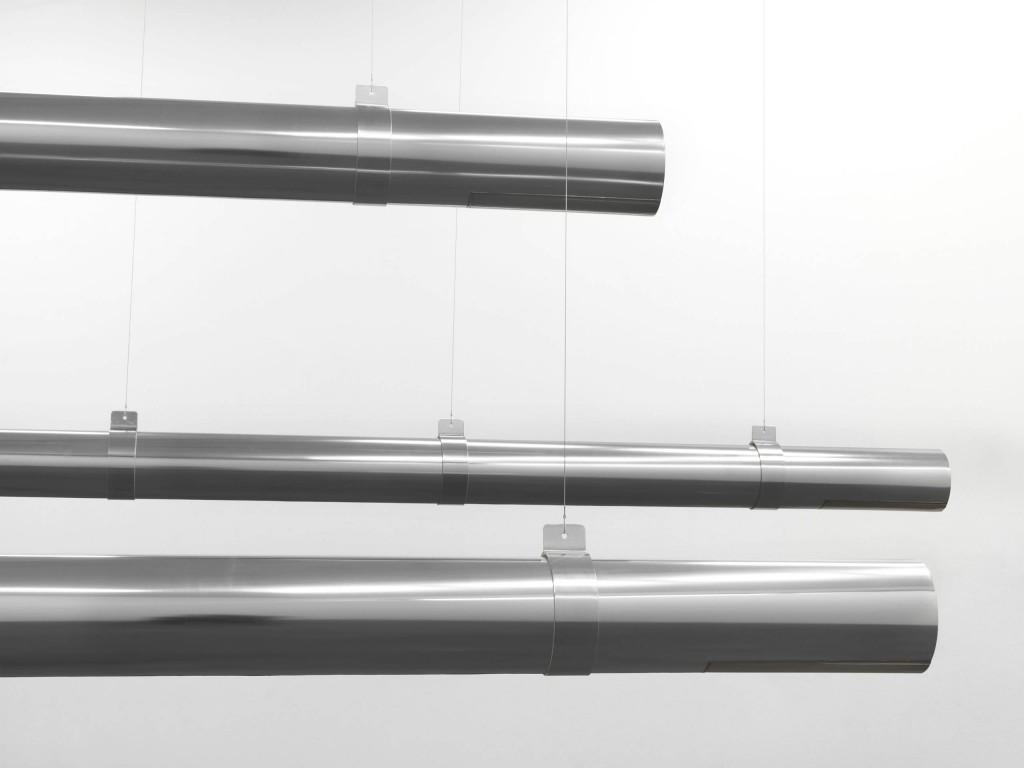

Such automatic weather stations, now connected by digital networks, are the basis of modern meteorology— and of Das Numen Meatus. Thousands upon thousands of them dot the planet today and the data from many is freely available. Das Numen now gather live wind speed and direction data from twenty such stations and feed it into a computer program that converts it into impulses. The latter in turn control valves in six organ pipes horizontally suspended in mid-air in the Berlin showroom of Galerie Dittrich & Schlechtriem. Compressed air—wind, in the parlance of organ builders—flows through the five flue pipes and one reed pipe, which produce various sounds as the impulses modify the valve settings. The air within the pipe resonates; an air column begins to vibrate. The length of the air column determines the pitch. The principle is the same as in a conventional organ, with the significant difference that there are no scores and no organist. All there is is the wind.

The stronger the wind in a given part of the world, the more pipes we hear; when it subsides, their sound grows brittle. The visitor hears the weather of the entire world, hears the atmosphere. Das Numen Meatus (from the Latin meatus, “the path”) balances on the line between science and subjectivity—the work is neither a scientific portrayal of the phenomenon we call weather nor a purely subjective articulation of the artists’ real experiences: no one describes in lyrical phrases how the wind picks up and abates, and yet the parameters are ultimately subjective and not meant to prove anything. Das Numen defined the placement, sizes, and configuration of the organ pipes and recruited the assistance of Raphael Jakobs at Laukhuff und Killinger Orgelpfeifen, Berlin, to build the ensemble.

Size, arrangement, and material are the parameters that determine an organ’s timbre. The five flue pipes with lengths ranging from 13.8 to 15.7 feet and the slightly louder reed pipe are tuned to the of the chromatic scale, separated by semitones, a temperament familiar to Western ears. The surrounding space is another vital component of the installation Das Numen Meatus: there is no sound without a resonance chamber; without air there is no resonance, no wind, no climate. And life as we know it would not exist without the atmosphere. No one hears the winds on Jupiter, and to hear them we would first have to abstract them and translate them into another system the way meteorological stations translate the earth’s weather. Das Numen Meatus is an abstraction cast into concrete reality.

SPACE AS SONIC MEMORY

Wind resonates and reasons. The weather, we might say, mulls over itself (which is not to say that we can read its thoughts). Standing before the organ pipes, we hear what is in itself inaudible: warming and cooling air masses moving toward equilibrium in a process that generates what we call wind. The sun shines on seas and landmasses, the earth rotates, the moon’s gravitational force tugs at everything. Far from being purely local and short-lived, winds travel around the world, across continents and seas: like the first observation of the Jupiter storm, that is an insight we owe to seventeenth-century England. In 1686, Robert Hooke’s colleague Edmond Halley (1656–1741) drew the first global weather map, charting the prevailing trade and monsoon winds. Halley—the man after whom the comet is named—argued that the direction and strength of the winds resulted from the warming of water and land in the various regions of the earth. Wind, he realized, was a global and local phenomenon.

What does that mean? Wherever we may go on the planet, we can hear it whistling, soughing, and rustling, in treetops and over wide plains, in tiny rock crevices and around tall mountain summits. Wind lets the negative spaces of our earth resound: the globe as a haunted house filled with sighs and murmurs. Climate is global, everything is connected to everything by oceans and air. And yet no one can hear different winds in various far-flung corners of the world at the same time—except here, in Das Numen Meatus.

Halley and Hooke, we might say, are the ancestors of what the artists of Das Numen undertake with their installation. But theirs is not a work of science; it is about sensory experience, about aesthetics. Sound is a physical phenomenon, but it is also what beings who have the sense for it experience. Then, too, sound is always presence; it lets us sense a space. “Meatus” presents the world to us as a musical instrument—a defined resonance chamber edged by the voiceless vacuum of outer space. And this resonance chamber is quite narrow: if you imagine the earth as a sphere the size of a soccer ball, the atmosphere is roughly as thick as a layer of film wrap.

If we hope to breathe freely tomorrow, we had best treat our climate the way a musician handles his instrument. Human beings exist only because there is weather, but they do not subsist wherever there is weather. In other words: we need the weather more than it needs us. We need wind to live. Das Numen create a space that is connected to twenty other—open—spaces around the world and picks up their vibrations. The six organ pipes communicate physical space in a space of art. Unlike the people of earlier centuries who imagined the nature they confronted as an unswayable and almighty power, we now know that we do in fact shape the earth’s weather and climate. The density and height of the buildings in major urban areas, for example, influence the local winds; civilization creates deserts; the greenhouse effect alters ocean currents; ice melts. We live in the Anthropocene.

We know a great deal about our climate, about the weather and geography of the earth, but to know is not yet to experience. We can tell how strongly and from which direction the wind is blowing at almost any location on the planet and at any time, we can tell how humid it is in Cape Town and how long the sun will shine today in Vladivostok. But what do we do with this knowledge? An adequate theory of the weather and reliable forecasts require abstraction from personal experience and faith in instruments. Das Numen do not forecast or record anything; they are not meteorologists. Their installation plays out in real time, like all experience. It renders the wind audible: the sound of the organ pipes as an ephemeral echo of the weather, a chorus of the earth in six parts, live.

1 Robert Hooke, “A Spot in One of the Belts of Jupiter,” Philosophical Transactions 1, no. 1 (March 6, 1665): 3, doi:10.1098/rstl.1665.0005.

2 Maurice Crewe, “The Fathers of Scientific Meteorology—Boyle, Wren, Hooke and Halley: Part 1,” Weather 58 (2003); http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1256/wea.95.02B/abstract.

Robert Hooke (1635–1702) war wie sein Zeitgenosse Isaac Newton ein Universalgenie des 17. Jahrhunderts (und lange dessen heute weit weniger bekannter Konkurrent). Eigentlich sollte Hooke nach dem Selbstmord seines Vaters Kunstmaler werden, konnte aber den Geruch der Ölfarbe nicht ertragen. Er wurde lieber Wissenschaftler und interessierte sich als solcher praktisch für alles: Er baute eine Tauchglocke, Mikroskope und Fernrohre, experimentierte mit Bluttransfusionen, erkannte die Wabenstruktur von Insektenaugen, prägte den Begriff der Zelle – und legte die Grundlagen der modernen Meteorologie. Seine Schrift „A Method for Making a History of the Weather“ von 1663 enthielt die ersten schlüssigen und ausführlichen Anleitungen zur Wetterbeobachtung und wurde ein halbes Jahr später der Royal Society vorgetragen, einer Gelehrtenvereinigung, deren Mitglied er war. Hooke sollte für sie das Wetter beobachten, um es eventuell vorhersagen zu können. Er entwickelte dazu mehrere meteorologische Instrumente. 1679 konstruierte er eine komplette Wetterstation. Hookes Wetteruhr zeichnete Windgeschwindigkeit, Niederschlagsmenge, Temperatur, Luftfeuchtigkeit und Luftdruck auf einem Papierstreifen auf – und zwar automatisch. Die Idee, die Wetterbeobachtung zu automatisieren und der subjektiven Notation durch einen Menschen zu entziehen, war ihrer Zeit dreihundert Jahre voraus.2 Hooke erkannte auch, dass es nötig war, das Wetter mit einem Netzwerk von solchen Stationen zu beobachten – möglichst weltweit.

Auf solchen automatischen und nunmehr digital vernetzten Wetterstationen basiert die moderne Meteorologie – und die Arbeit Das Numen Meatus. Abertausende von ihnen sind heute über den Planeten verteilt, ihre Daten oft frei abrufbar. Von zwanzig solcher Stationen erfasste Windgeschwindigkeiten und -richtungen werden von Das Numen nun live erhoben und mittels einer Software in Impulse umgerechnet. Diese wiederum steuern Ventile in sechs waagerecht in der Luft hängenden Orgelpfeifen im Berliner Ausstellungsraum der Galerie Dittrich & Schlechtriem. Komprimierte Luft – im Orgelbau Wind genannt – strömt durch die fünf Labial- und eine Zungenpfeife, die durch die Dank der Impulse wechselnden Ventilstellung zum Klingen gebracht werden. Die Luft im Pfeifenkörper wird zum Klingen gebracht, eine Luftsäule in Schwingungen versetzt. Die Länge der Luftsäule bestimmt dabei die Tonhöhe. Das Prinzip ist das einer herkömmlichen Orgel, mit dem bedeutenden Unterschied, dass es keine Partitur gibt und keinen Organisten. Es gibt nur den Wind.

Je stärker der Wind in der betreffenden Weltregion ist, desto mehr Pfeifen ertönen, bei schwachem Wind wird ihr Klang brüchig. Man hört das Wetter der ganzen Welt, man hört die Atmosphäre. Das Numen Meatus („meatus“ lat.: der Pfad) oszilliert insofern zwischen Wissenschaftlichkeit und Subjektivität, als die Arbeit weder eine naturwissenschaftliche Beschreibung des Phänomens Wetter ist noch rein subjektiv auf realen Erfahrungen der Künstler beruht: Niemand beschreibt in lyrischen Worten, wie der Wind sich hebt und senkt, und doch sind die Parameter letztlich subjektiv und wollen nichts beweisen. Anordnung, Größe und Einstellung der Orgelpfeifen wurden von Das Numen definiert und das Ensemble mit Unterstützung von Raphael Jakobs bei Laukhuff und Killinger Orgelpfeifen in Berlin gebaut.

Größe, Anordnung und Material sind die Parameter, die den Klang bestimmen. Die fünf zwischen 4,20 und 4,80 Meter langen Labialpfeifen und die etwas lautere Zungenpfeife folgen der chromatischen Tonleiter in Halbtonschritten, wie sie einem Rezipienten aus dem westlichen Kulturraum vertraut ist. Eine weitere wichtige Komponente der Installation Das Numen Meatus ist der sie umgebende Raum: ohne Resonanzraum entsteht kein Klang, ohne Luft gibt es keine Resonanz, keinen Wind, kein Klima. Ohne Atmosphäre gibt es auch kein Leben, wie wir es kennen. Die Winde auf Jupiter hört niemand, und wenn man sie doch hören wollte, dann müsste man sie erst abstrahieren und in ein anderes Systems übersetzen, wie die Wetterstationen es auf der Erde tun. Das Numen Meatus ist die Konkretisierung einer Abstraktion.

RAUM ALS KLANGGEDÄCHTNIS

Der Wind resoniert und räsoniert. Das Wetter denkt sozusagen über sich selbst nach (nicht, dass man es deshalb verstehen könnte). Man hört, vor den Orgelpfeifen stehend, was man eigentlich nicht hören kann: die sich erhitzenden und abkühlenden Luftmassen, deren Druckunterschiede sich ausgleichen und dabei etwas erzeugen, was wir als Wind bezeichnen. Meere und Landmassen werden von der Sonne beschienen, die Erde dreht sich, der Mond zerrt an allem. Dass Winde nicht nur lokale, kurzlebige Phänomene sind, sondern über Kontinente und Meere hinweg um die Welt wehen, dieses Wissen verdanken wir wie das um den Jupitersturm dem England des 17. Jahrhunderts. Edmond Halley (1656–1741), ein Kollege von Robert Hooke, zeichnete 1686 die erste Wetterkarte der Erde mitsamt den vorherrschenden Passatund Monsunwinden. Halley, nach dem auch der Komet benannt ist, begründete ihre Richtung und Stärke mit der Aufheizung von Wasser und Land in den jeweiligen Erdregionen. Wind, begriff er, war ein globales und ein lokales Phänomen.

Was heißt das? Überall auf der Welt pfeift, rauscht und knistert es, ob in Baumkronen oder über weiten Ebenen, in winzigen Felsspalten oder um hohe Berge. Die Negativräume unserer Erde werden vom Wind vertont: der Globus als haunted house, in dem es überall seufzt und brummt. Das Klima ist global, alles mit allem verbunden durch Ozeane und Luft. Doch niemand kann verschiedene Winde an verschiedenen Enden der Welt gleichzeitig hören – nur hier bei Das Numen Meatus.

Halley und Hooke sind sozusagen die Urgroßväter dessen, was die Künstler von Das Numen mit ihrer Installation unternehmen. Aber hier geht es nicht um Wissenschaft, sondern um sinnliche Erfahrung, um Ästhetik. Klang ist ein physikalisches Phänomen, aber auch die sinnliche Erfahrung dafür ausgestatteter Wesen. Klang ist immer auch Präsenz, am Klang lässt sich ein Raum erkennen. „Meatus“ stellt uns die Erde als Instrument vor – sie ist ein definierter Resonanzraum, den der klanglose, luftleere Weltraum begrenzt. Und dieser Resonanzraum ist ziemlich schmal: Stellt man sich die Erde als fußball- großen Globus, dann ist die Atmosphäre etwa so dick wie Frischhaltefolie.

Wer morgen immer noch durchatmen will, behandelt sein Klima am besten wie der Musiker sein Instrument. Menschen gibt es nur, weil es Wetter gibt, aber nicht überall, wo es Wetter gibt existieren, auch Menschen. Wir brauchen, in anderen Worten, das Wetter mehr, als es uns braucht. Wir brauchen Wind, um zu leben. Das Numen schaffen einen Raum, der mit zwanzig anderen – offenen – Räumen auf dieser Welt verbunden ist und sich von ihnen in Schwingung versetzen lässt. Die sechs Orgel- pfeifen vermitteln den physikalischen Raum in einem Raum der Kunst.

Anders als in der Vorstellung früherer Jahrhunderte, in denen der Mensch der Natur als einer unbeeinflussbaren Allmacht gegenüberstand, wissen wir heute, dass wir Wetter und Klima der Erde sehr wohl beeinflussen. Der Grad und die Höhe der Bebauung in großen Stadträumen etwa beeinflussen den dortigen Wind, die Zivilisation schafft Wüsten, Meeresströmungen verändern sich durch den Treibhauseffekt, Eis schmilzt. Wir leben im Anthropozän. Wir wissen viel über unser Klima, das Wetter und die Geographie der Erde, aber Wissen ist nicht dasselbe wie Erfahrung. Rund um die Uhr an beinahe jedem Ort kann man sagen, wie stark der Wind weht und aus welcher Richtung, man kann die Luftfeuchtigkeit von Kapstadt angeben und die Sonnenscheindauer in Wladiwostok. Was aber machen wir mit diesem Wissen?

Um gültige Aussagen und Vorhersagen über das Wetter zu machen, muss man von persönlichem Erleben abstrahieren und den Instrumenten vertrauen. Das Numen sagen nichts voraus und zeichnen nichts auf, sie sind keine Meteorologen. Ihre Installation vollzieht sich in Echtzeit, wie jedes Erleben. Sie lässt den Wind hörbar werden: der Klang der Orgelpfeifen als ephemerer Widerhall des Wetters, ein sechsstimmiger Chor der Erde, live.

____________

1 Robert Hooke, „A Spot in One of the Belts of Jupiter“, in: Philosophical Transactions, Band 1, Nummer 1, 6. März 1665, S. 3, doi:10.1098/rstl.1665.0005.

2 Maurice Crewe, „The Fathers of Scientific Meteorology – Boyle, Wren, Hooke and Halley: Part 1“, in: Weather, Band 58 (2003); http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1256/wea.95.02B/abstract.